On 9 January 2025, China’s Ministry of Commerce (“MOFCOM”) concluded its six-month investigation into the practices of the European Commission (“Commission”) in relation to the Foreign Subsidy Regulation (“FSR”) of the European Union (“EU”) pursuant to China’s Foreign Trade Law[1] and the Foreign Trade Barrier Investigation Rules[2].

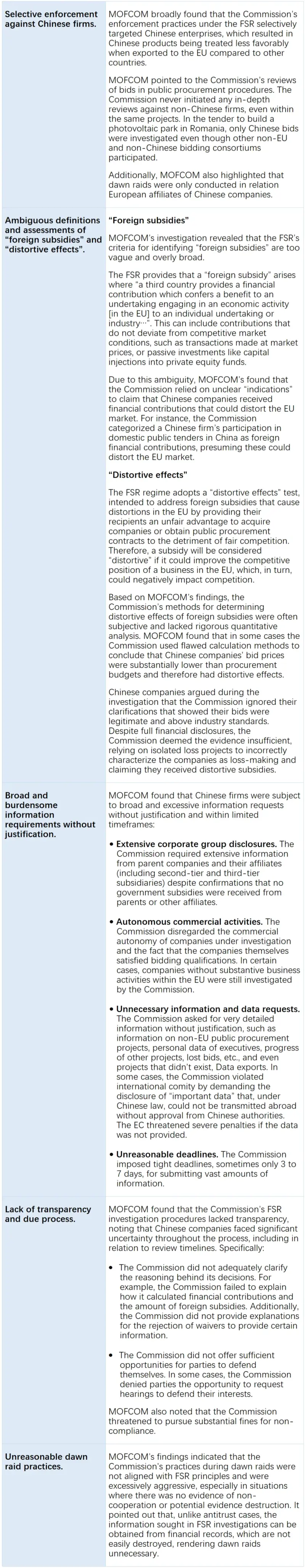

Specifically, MOFCOM found that the FSR constituted a “trade barrier” as stipulated in Foreign Trade Barrier Investigation Rules, harming the competitiveness of Chinese enterprises operating in the EU.[3] MOFCOM found that the Commission’s practices in conducting FSR reviews and investigations (i) selectively targeted Chinese companies; (ii) relied on ambiguous definitions in the assessment of “foreign subsidies” and “market distortions”; (iii) imposed an overly broad scope for FSR investigations and created burdensome information requirements; (iv) lacked transparency, causing significant uncertainty for notifying or investigated parties; (v) made use of dawn raids that were disproportionate to the subject matter of the investigation; (vi) engaged in other unreasonable practices, including by imposing reversed burden of proof and threatening severe penalties for non-compliance and lack of cooperation. In light of these findings, MOFCOM has stated its intention to pursue bilateral negotiations and other appropriate measures to urge the EU to modify its FSR practices, ensuring that Chinese companies can invest and operate in the EU fairly and without discrimination.[4]

Since the FSR’s inception in late 2023, almost all in-depth reviews and investigations initiated by the Commission so far have involved Chinese companies. During this time, the EU has also released a 700+ page report on state-induced distortions on China’s economy by focusing on specific sectors, which could act as a blueprint for future investigations.[5] In parallel, the European Commission has also brought investigations under other statutory instruments, including the EU’s anti-subsidy rules[6] and the International Procurement Instrument (“IPI”).

Please check the PDF version here.

Background and context

The FSR came into force on 12 July 2023 with the goal of regulating foreign subsidies that may distort the EU market in the context of M&A transactions, public procurement projects and other market situations. The Commission administers the FSR through three tools as set out in Table 1 below. The Commission’s practices in relation to administering these tools were heavily criticized in MOFCOM’s decision.

Table 1: Commission’s FSR tools

The review process for M&A and public procurement notifications includes pre-notification, a preliminary review (Phase I), and (if necessary) an in-depth investigation (Phase II). The Commission may initiate an in-depth investigation if there are sufficient “indications” during the Phase I review that a transaction party has been granted a foreign subsidy that distorts the EU market. MOFCOM has expressed criticism regarding the Commission’s decisions so far to initiate in-depth reviews based solely on its views on the presence of “indications” of market distortions.

In terms of the general investigations tool, the Commission can issue information requests and conduct interviews relating to the subject matter of the investigation. The Commission can also conduct dawn raids and other inspections within the EU but also within the territory of the third-country such as China (but only with the consent of the government). MOFCOM’s decision highlights concerns regarding the broad scope of investigations, including the use of dawn raids and information requests that seem disproportionate to the subject matter being investigated.

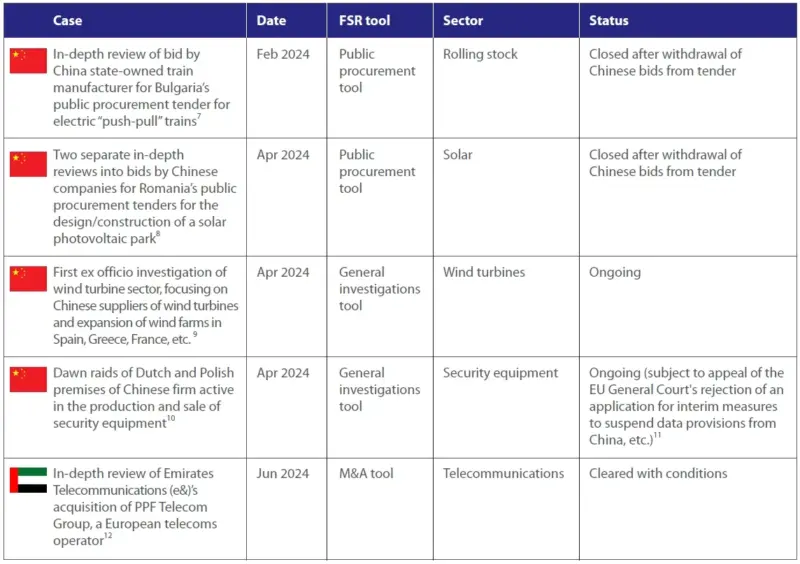

Key FSR investigations and related developments

Since its inception, almost all in-depth reviews and ex officio investigations under the FSR involved Chinese companies, which MOFCOM has criticized as selective enforcement against Chinese firms.

Table 2: In-depth FSR investigations to date

Other related developments

In addition to the reviews and investigations initiated by the Commission under the FSR to date:

- in October 2023, the EU launched related investigations into China’s electric vehicles under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures;

- in April 2024, the Commission released a 700+ page report on state-induced distortions on China’s economy in a range of sectors, including iron and steel, aluminium, chemicals, ceramics, telecommunications, semiconductors, rail vehicles, environmentally friendly products (renewable energy), and new energy vehicles.

- in April 2024, the EU also launched an IPI investigation into the public procurement arrangement of medical equipment in China, which, according to the EC press release, was in response to measures and practices in the Chinese procurement market for medical devices which discriminate unfairly against EU companies and products.

Legal basis of MOFCOM investigation

China’s Foreign Trade Law has the goal of developing foreign trade, maintaining a foreign trade order, and protecting the legal rights of foreign trade dealers.

Articles 36 and 37 of the Foreign Trade Law provide that the foreign trade department of the State Council may investigate trade barriers of relevant countries or regions by way of written questionnaires, hearings, on-site investigations, commissioned investigations, etc. The foreign trade department must announce the start of a foreign trade investigation and report on its findings.

What is a “trade barrier”?

Based on China’s Foreign Trade Law, MOFCOM has formulated Foreign Trade Barrier Investigation Rules, which provide details of the definition of a “trade barrier” and the procedure for conducting related investigations.

Article 3 of the Foreign Trade Barrier Investigation Rules provides that measures or activities made or supported by the governments of foreign countries/regions are trade barriers if the measures or activities (i) cause unreasonable harm to the competitiveness of products/services originating from China in the foreign market; and/or (ii) violate or fail to implement obligations pursuant to bilateral trade agreements with China, among other factors.

Initiation of MOFCOM investigation

MOFCOM can either initiate the trade barrier investigation at the request of applicants, or initiate the trade barrier investigation by itself.[13]

On 17 June 2024, the China Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export of Machinery and Electronic Products (“CCCME”) submitted an application to MOFCOM to initiate a trade and investment barrier investigation under China’s Foreign Trade Law.[14] The CCCME was concerned that the EU (through the Commission) conducted FSR reviews and investigations that targeted Chinese enterprises in an unreasonable and discriminatory manner, preventing their entry into the EU market and harming their competitiveness.

On July 10, 2024, MOFCOM launched an investigation into the Commission’s FSR practices. In the following six months, MOFCOM conducted extensive market testing involving government agencies, relevant Chinese companies, industry associations, and the EU Delegation in China. This included the use of questionnaires, public consultations, and on-site interviews with Chinese firms impacted by the FSR in industries like rolling stock, photovoltaic technologies, wind power, and security inspection equipment.

Consequences of identifying a “trade barrier”

There are no immediate legal or punitive consequences if MOFCOM makes a finding that certain measures or activities under investigation constitute “trade barriers”. MOFCOM’s findings often serve as a basis for further negotiations or discussions with foreign governments. Under the Foreign Trade Barrier Investigation Rules, MOFCOM merely has the opportunity to (i) hold bilateral negotiations; (ii) initiate a settlement mechanism of multilateral disputes; or (iii) take other appropriate measures. Therefore, whilst there may not be immediate consequences, the findings can have longer-term implications for trade relations and policies.

MOFCOM has typically pursued bilateral negotiations following trade barrier investigations under China’s Foreign Trade Law. This has included restrictions on laver imports into Japan (which the Japanese government later lifted);[15] the treatment of renewable energy products in the United States;[16] and, most recently, Taiwan’s ban on imports from Mainland China, which is reportedly being addressed through bilateral negotiations.[17]

Assessment and findings

MOFCOM considered that the Commission’s FSR investigations and practices constituted a “trade barrier” within the meaning of Article 3 of Foreign Trade Barrier Investigation Rules.

Impact of FSR investigations

MOFCOM’s investigation revealed that the Commission’s FSR investigations hindered or restricted the entry of Chinese products into the EU market and damaged their competitiveness. Therefore, the Commission’s practices were considered “trade barriers”. Specifically:

- Economic losses. FSR investigations led to both direct and indirect economic losses for Chinese enterprises, with (i) abandoned bidding projects valued at over RMB 7.6 billion (around EUR 1 billion); (ii) other affected projects exceeding RMB 8 billion (around EUR 1.063 billion); and (iii) additional losses related to bid guarantees, compensation payments, and compliance expenses amounting to over RMB 100 million (EUR 13.3 million).

- Exclusion of Chinese firms. FSR-related practices led to the exclusion Chinese companies from bidding opportunities in the EU. Some EU member states imposed additional requirements in tenders, disqualifying Chinese firms or their affiliates based on qualifications, technical standards, or “national security threats”. Some EU tenders also included termination clauses targeting Chinese enterprises, providing for contract cancellation without compensation if distortive foreign subsidies were identified.

- Compliance and reputational costs. More broadly, the combination of FSR investigations with antitrust and foreign investment reviews significantly increased compliance costs and legal risks for Chinese firms operating and investing in the EU. Chinese firms were forced to allocate additional manpower, resources and finances to manage FSR compliance. FSR investigations have also led to reputational damage for Chinese firms. For example, delays in contract confirmations stemming from FSR investigations could result in lost customers and missed collaboration opportunities due to increased perceptions of risk and caution.

Industry associations taking part in the MOFCOM investigation observed a decline in exports of photovoltaic products to the EU and that more sectors have been forced to adjust their export and investment plans due to concerns about the impact of the FSR.

Concluding remarks

MOFCOM’s criticisms of the FSR are neither new nor unexpected. The original White Paper that introduced the concept of an FSR regime included references to various OECD reports that indicated widespread government interventions in China, in particular (e.g. aluminum; semiconductors). Then, in the lead up to the FSR’s implementation, many commentators highlighted various ambiguities and uncertainties related to its practical and procedural elements. This included issues such as the inclusion of financial contributions obtained under normal market conditions or the use of “indicators” for assessing distortive effects, which were scrutinized in the MOFCOM investigation. Some of these aspects were partially clarified by the Commission in a separate Staff Working Document published in July 2024 (see our separate update).

The Commission is required, by law, to publish further guidelines on the FSR’s practical application by 12 January 2026. The Commission may have the opportunity to address the concerns raised in MOFCOM’s investigation when it next reviews its FSR practices and provides further guidance. Given the number of Chinese firms affected by the FSR and the range of stakeholders and sectors involved in the MOFCOM investigation, it will be difficult to ignore MOFCOM’s findings. More broadly, the experience of Chinese firms facing FSR reviews and investigations confirms and underscores the importance of building comprehensive compliance systems to (i) record and count financial contributions centrally; and (ii) assess financial contributions for notifications and investigations. An ongoing internal compliance system will help support credibility of any calculations and reportable financial contributions submitted to the Commission.

- * The authors would like to thank Max Lu for his research contributions.Foreign Trade Law of the People’s Republic of China, Decree No. 128 of the President of the People’s Republic of China. ↑

- Order of the Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China No. 4 of 2005. ↑

- MOFCOM Trade Remedy and Investigation Bureau, Ministry of Commerce Announcement No. 3 of 2025, see: https://www.mofcom.gov.cn/zcfb/zc/art/2025/art_2dca63bcd6b0433ba71c14e9b9885ee6.html. ↑

- See, https://www.mofcom.gov.cn/xwfbzt/2025/swbzklxxwfbh2025n1y9r/index.html. ↑

- See, https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/news/commission-updates-report-state-induced-distortions-chinas-economy-2024-04-10_en. ↑

- REGULATION (EU) 2016/1037 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCILof 8 June 2016 on protection against subsidised imports from countries not members of the European Union. ↑

- See, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_887. ↑

- See, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_1803. ↑

- See, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_24_1927. ↑

- See, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/mex_24_2247. ↑

- See, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/C/2024/5824/oj/eng. ↑

- See, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3166. ↑

- Article 4, Foreign Trade Barrier Investigation Rules. ↑

- See, https://www.mofcom.gov.cn/cms_files/filemanager/1511035453/attach/20247/cf679492333441e88b6044d178b0f39f.pdf. ↑

- See, https://m.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/c/200502/20050200019196.shtml. ↑

- See, https://m.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/c/201208/20120808293989.shtml. ↑

- See, http://file.mofcom.gov.cn/article/zcfb/gpmy/202312/20231203460950.shtml. ↑